Abstract

The majority of cases of autosomal-dominant retinitis pigmentosa (adRP) are associated with rhodopsin (RHO) variants. More than 290 pathogenic variants responsible for 25%–30% of adRP cases have been identified to date. This retrospective report focuses on RHO and RP cases in the Brazilian population. Patients with molecular confirmation of pathogenic variants in the RHO gene were included. Their clinical and genetic data were analyzed. Segregation analyses were included where possible. Cases were classified as generalized RP or sector RP according to fundus examinations and imaging data. The medical records of 43 patients from 34 families with RHO-associated RP were reviewed. Twenty-two disease-causing variants of the RHO gene and four previously unreported variants (c.317G>T; c.937-2A>T, c.272_283del, and c.530+1G>C) were identified. The majority of cases involved missense variants. The most prevalent variant was c.551A>G, p.(Gln184Arg), which was identified in seven patients (21%) from four families. One patient presented with the splice donor variant c.530+1G>C in the homozygous state, which was classified as pathogenic. Thirty-two patients presented with a generalized RP phenotype, and six patients were diagnosed with sector RP. This study provides information on the clinical and genetic features of RHO-associated RP in the Brazilian population, expanding the spectrum of RHO gene disease-causing variant frequencies.

Impact statement

RHO is one of the most frequently implicated genes in autosomal-dominant Retinitis Pigmentosa, yet most existing data come from non-Latin American populations. By identifying and characterizing RHO variants and their allele frequencies in Brazilian patients, this work expands the international catalog of RHO mutations and refines genotype–phenotype correlations in a diverse genetic background. The discovery of novel and population-specific variants provides critical information for accurate genetic diagnosis, counseling, and variant interpretation in Brazil. This study enhances clinical and research capacities by improving molecular diagnosis, informing patient selection for gene-specific therapies, and contributing to equitable representation in global RP studies. Ultimately, these findings strengthen the foundation for precision medicine and future therapeutic advances in inherited retinal diseases.

Introduction

Rhodopsin is a photopigment molecule and the most abundant protein in rod photoreceptors. It is primarily affected in retinitis pigmentosa (RP). By the late 1980s, rhodopsin was one of the best-understood visual proteins in terms of its structure, biochemistry, and genetics [1]. The rhodopsin gene (RHO) was the first gene for which RP-associated variants were identified [2]. Large families with autosomal-dominant RP (adRP) have been studied for linkages. The first link between RP and the RHO locus was reported in 1989, and mutations in RHO were identified in 1990 [3].

RHO-associated RP accounts for 20-30% of adRP cases [4], and approximately 4% of all RP [5] cases; more than 290 disease-causing RHO variants have been identified according to the ClinVar [6], UniProt [7], and Franklin Community Databases [8].

The most frequent phenotypes linked to RHO-associated RP are the generalized (classical) form and the sector form. While sector RP tends to progress more slowly than the generalized type, multiple studies have reported that it can ultimately develop into a generalized form [9, 10]. RHO variants have also been found in the autosomal-recessive (arRP) forms of RP [11].

Rhodopsin plays an essential role in the visual process, and even minor errors during gene transcription, translation, folding, processing, or transport to the correct cellular location can impair vision [12]. Previous studies have shown that the clinical features of RHO-associated RP correlate with specific protein domains affected by mutations [13].

This retrospective study explores the molecular mechanisms and phenotypic spectrum of RHO-associated RP in a Brazilian population.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, with strict protection of patient identity, and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de São Paulo (protocol number 5.113.810). Written informed consent was obtained where necessary to perform the molecular tests. During DNA sample collection for molecular testing, all the patients and/or their legal guardians provided written informed consent for the use of their personal medical data for scientific purposes and publication.

This observational retrospective study was performed. The inclusion criterion comprised genetically confirmed RHO-associated RP retrieved from the medical records of different ophthalmological centers in Brazil. Patient data from ophthalmological, genetic, clinical, and imaging records were evaluated. Genetic analysis was performed using commercial next-generation sequencing (NGS) panels for inherited retinal disorders, which included either 224 or 330 genes. Three of the most common genetic testing laboratories that were used were Invitae Laboratory, Mendelics, and Dasa Genomica. These genetic testing laboratories are accredited by the College of American Pathologists (CAP) and the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA). The pathogenicity of each variant was classified according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) [14]. The RHO transcript ID is NM_000539.3. Two platforms combine computational predictions with clinical support, segregation, or functional studies to assist in variant classification. Both use sets of rules that follow the ACMG criteria: Franklin (https://franklin.genoox.com) and Varsome (https://varsome.com). Both were accessed on 25 October 2025. The identified variants were compared with records in ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/; accessed on 25 October 2025). Segregation analyses were performed where available.

For all variants with sufficient evidence, the classification followed the system proposed by Athanasiou et al.: [15] Class 1: variants affecting post-Golgi trafficking and outer segment (OS) targeting; Class 2: variants involving misfolding, endoplasmic-reticulum (ER) retention, and protein instability; Class 3: variants disrupting vesicular trafficking and endocytosis; Class 4: variants altering post-translational modifications and reducing protein stability; Class 5: variants impairing transducin activation; Class 6: variants leading to constitutive receptor activation; and Class 7: variants resulting in dimerization deficiency.

Results

Forty-three patients from 34 families with conclusive molecular genetic testing were identified as having RHO-associated RP. A total of 22 disease-causing variants of the RHO gene were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic. Four of these variants were previously unreported and were each identified in a different family (c.317G>T, c.937-2A>T, c.272_283del, and c.530+1G>C).

Clinical characteristics

Six patients presented with a sector RP phenotype, and 32 patients presented with classical RP. One patient was an asymptomatic carrier and was evaluated for family history. Twenty-five patients had a positive family history (8 patients had an affected father, 8 patients had an affected mother, and 9 patients had an affected relative, such as a son, daughter, or cousin). The age at onset ranged from 5 to 38 years, with nyctalopia being the most common symptom. The best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) ranged from 20/25 to 20/800. Eight patients presented with cystoid macular edema (CME) during the clinical course. The clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Patients (n = 38) | Generalized RP (n = 32) | Sector RP (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|

| Families | 26 | 5 |

| Gender Male Female | 12 (36.0%) 21 (63.0%) | 3 (50.0%) 3 (50.0%) |

| Age of onset, mean (SD), years | 18.1 (10.08) | 27.5 (17.67) |

| First symptom | Nyctalopia (54.0%) | Nyctalopia (20.0%) |

| Baseline BCVA, mean (SD), LogMAR | 0.43 (0.40) OD; 0.50 (0.50) OS | 0.28 (0.31) OD; 0.08 (0.09) OS |

| Cystoid macular edema (CME) | 7 (21.0%) | 1 (20.0%) |

Clinical characteristics of RHO-associated RP patients.

Molecular diagnosis

The majority of variants were missense (19 variants, 86.0%); the remainder included two splicing variants and one in-frame deletion. The most prevalent variant was c.551A>G, p.(Gln184Arg), which was identified in seven patients (21.0%) from four families. One patient presented with the homozygous splice donor variant c.530+1G>C, which was classified as pathogenic; subsequently, segregation analysis was conducted. Table 2 summarizes the variants and allele frequencies observed in this cohort (Supplementary Table S1).

TABLE 2

| Nucleotide change | Protein change | Allele frequency (families) | Variant type | GnomAD total allele freq (%)a | ACMG classification/criteria | First report |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.45T>G | p.(Asn15Lys) | 1 (1) | Missense | - | Likely pathogenic/PS1, PM2, PM5, PP3 | [16] |

| c.137T>G | p.(Leu46Arg) | 3 (1) | Missense | - | Pathogenic/PS4, PM1, PM2, PP3 | [17] |

| c.272_283del | p.(Thr92_Leu95del) | 1 (1) | In-frame deletion | - | Likely pathogenic/PM1, PM2, PM4 | This study |

| c.316G>A | p.(Gly106Arg) | 4 (4) | Missense | 0.000411 | Pathogenic/PS1, PS3, PM1, PM2, PM5 | [18] |

| c.317G>T | p.(Gly106Val) | 4 (3) | Missense | - | Likely pathogenic/PM2, PM5, PP2, PP3, PP5 | This study |

| c.341G>T | p.(Gly114Val) | 1 (1) | Missense | - | Likely pathogenic/PM1, PM2, PM5, PP3, PP5 | [19] |

| c.403C>T | p.(Arg135Trp) | 5 (2) | Missense | 0.000137 | Likely pathogenic/PM1, PM2, PM5, PP3, PP5 | [20] |

| c.404G>T | p.(Arg135Leu) | 1 (1) | Missense | - | Likely pathogenic/PM1, PM2, PM5, PP3, PP5 | [21] |

| c.491C>T | p.(Ala164Val) | 1 (1) | Missense | 0.0003979 | Pathogenic/PS4, PM2, PM5, PM1, PP2, PP5 | [15] |

| c.509C>G | p.(Pro170Arg) | 1 (1) | Missense | 0.0000684 | Pathogenic/PS3, PM1, PM2, PM5, PP3 | [18] |

| c.512C>A | p.(Pro171Gln) | 1 (1) | Missense | - | Pathogenic/PS3, PM1, PM2, PM5, PP3 | [18] |

| c.512C>T | p.(Pro171Leu) | 1 (1) | Missense | - | Pathogenic/PS3, PM1, PM2, PM5, PP3 | [18] |

| c.530+1G>C | (p.?) | 2 (1) | Splicing | - | Pathogenic/PVS1, PM2, PP5 | This study |

| c.533A>G | p.(Tyr178Cys) | 1 (1) | Missense | 0.0000684 | Pathogenic/PS3, PM1, PM2, PM5, PP3 | [22] |

| c.551A>G | p.(Gln184Arg) | 7 (4) | Missense | 0.000657 | Likely pathogenic/PM1, PM2, PP2, PP3 | [23] |

| c.557C>G | p.(Ser186Trp) | 1 (1) | Missense | - | Likely pathogenic/PM1, PM2, PM5, PP2, PP3 | [24] |

| c.560G>C | p.(Cys187Ser) | 1 (1) | Missense | - | Likely pathogenic/PM1, PM2, PM5, PP2, PP3 | [25] |

| c.568G>A | p.(Asp190Asn) | 3 (3) | Missense | 0.000137 | Pathogenic/PS3, PM1, PM2, PM5, PP3 | [26] |

| c.800C>T | p.(Pro267Leu) | 1 (1) | Missense | 0.0000684 | Pathogenic/PS4, PM1, PM2, PM5, PP3, | [25] |

| c.937-2A>T | (p.?) | 1 (1) | Splicing | - | Pathogenic/PVS1, PM2, PP5 | This study |

| c.1033G>C | p.(Val345Leu) | 2 (2) | Missense | 0.0000684 | Pathogenic/PS1, PM1, PM2, PM5 | [15] |

| c.1040C>T | p.(Pro347Leu) | 1 (1) | Missense | 0.000137 | Likely pathogenic/PM1, PM2, PM5, PP3, PP5 | [27] |

Pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants of RHO-associated RP patients.

Accessed on December 2025.

Variant class

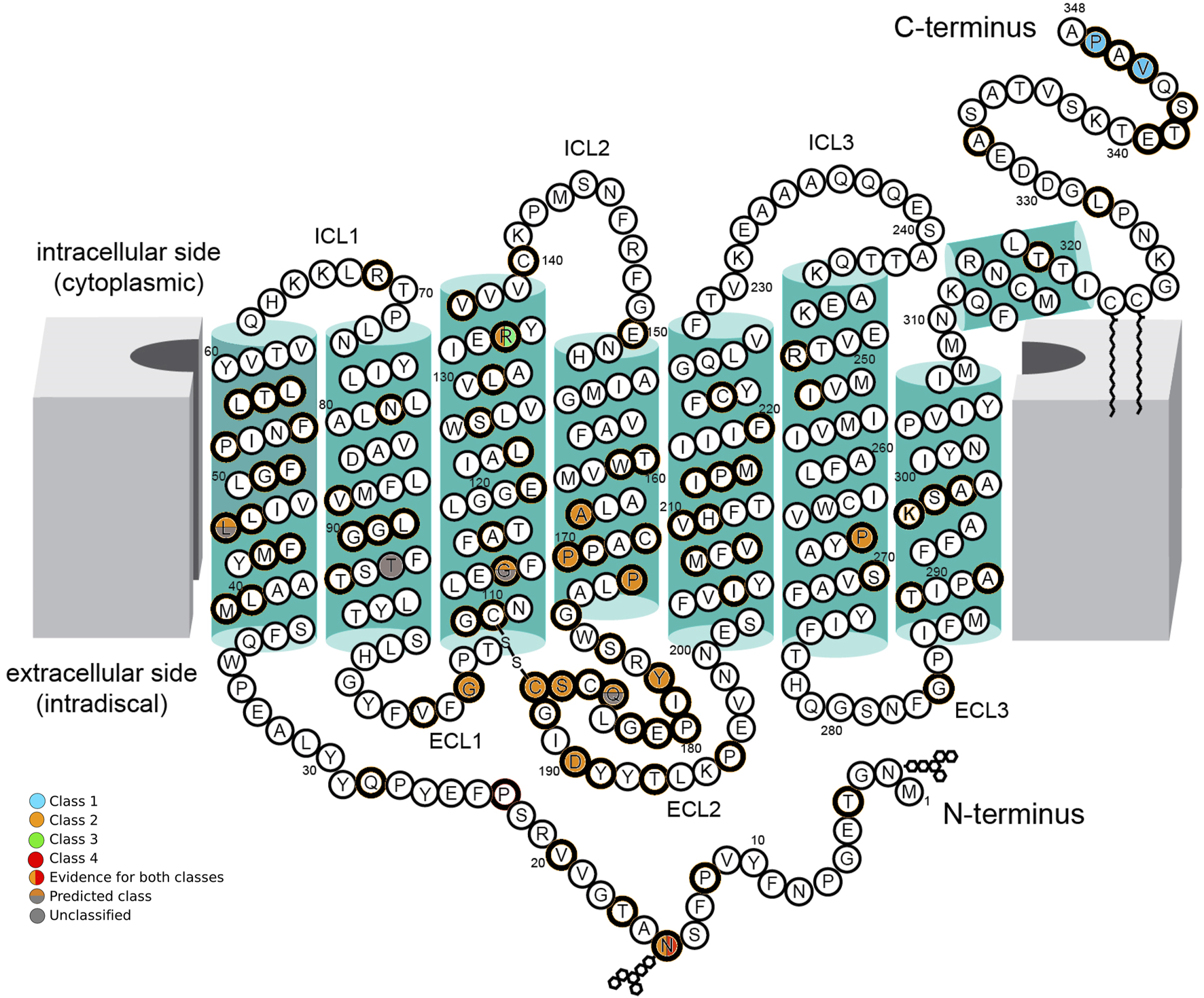

Two variants were classified as Class 1, eleven were classified as Class 2, one variant as Class 2/3, one variant as Class 2/4, three variants as unclassified predicted Class 2, and three variants remained unclassified (U) due to a lack of experimental evidence (Figure 1; Table 3). Class 2 was the most prevalent in this cohort. Twelve Class 2 patients presented with a generalized RP phenotype, five patients had a sector RP phenotype, and three patients were unavailable for clinical classification. Two patients harbored Class 1 variants and presented with generalized RP. Three variants were unclassified but predicted to be Class 2; five patients presented with a generalized RP phenotype, and one was an asymptomatic carrier. One patient harbored a variant combining classes 2 and 4 (Class 2/4) with generalized RP. Five patients harbored variants combining Classes 2 and 3 (Class 2/3), and all exhibited a generalized RP phenotype.

FIGURE 1

Schematic of the secondary structure of rhodopsin, Adapted from “Schematic rod photoreceptor and rhodopsin structure. (C) Two-dimensional representation of human Rho structure. Residues mutated in RP are indicated with orange circles. The Lys296, which covalently binds the 11-cis-retinal, is shown with a yellow circle filled with orange. The P23H mutation is shown with a red circle filled with orange” by Maria Azam and Beata Jastrzebska, licenced under CC BY 4.0. The seven-fold transmembrane helices, plus an eighth helix parallel to the membrane surface, are colored in green boxes. The intracellular side (cytoplasmic) contains three intracellular loops (ICL1, ICL2, and ICL3) and the carboxy-terminus (C-terminus) of the polypeptide chain. The extracellular side (intradiscal) contains the other three extracellular loops (ECL1, ECL2, and ECL3) and the amino-terminal end (N-terminus). The position of amino acid residues affected by RHO variants found in this cohort is indicated by colored circles. Class 1 variants (blue circles), Class 2 variants (orange circles), Class 3 variants (green circles), and Class 4 variants (red circles) are indicated with their location in the protein. Where there is evidence for more than one class type, it is shown with a vertical color split. Those with predicted effects are shown with a horizontal color split. Unclassified variants are indicated with gray circles.

TABLE 3

| Nucleotide change | Protein change | Location | Suggested class | Phenotype (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.45T>G | p.(Asn15Lys) | Intradiscal (N-terminal segment) | 2/4 | generalized RP (1) |

| c.137T>G | p.(Leu46Arg) | 1st alpha helix (TM1) | U/P2 | generalized RP (2) |

| c.272_283del | p.(Thr92_Leu95del) | 2nd alpha helix (TM2) | U | sector RP (1) |

| c.316G>A | p.(Gly106Arg) | Intradiscal (1st extracellular loop) | 2 | generalized RP (2)/sector RP (2) |

| c.317G>T | p.(Gly106Val) | Intradiscal (1st extracellular loop) | 2 | generalized RP (2)/sector RP (2) |

| c.341G>T | p.(Gly114Val) | 3rd alpha helix (TM3) | U/P2 | generalized RP (1) |

| c.403C>T | p.(Arg135Trp) | 3rd alpha helix (TM3) | 2/3 | generalized RP (5) |

| c.404G>T | p.(Arg135Leu) | 3rd alpha helix (TM3) | 3 | generalized RP (1) |

| c.491C>T | p.(Ala164Val) | 4th alpha helix (TM4) | 2 | N/A |

| c.509C>G | p.(Pro170Arg) | 4th alpha helix (TM4) | 2 | N/A |

| c.512C>A | p.(Pro171Gln) | 4th alpha helix (TM4) | 2 | generalized RP (1) |

| c.512C>T | p.(Pro171Leu) | 4th alpha helix (TM4) | 2 | generalized RP (1) |

| c.530+1G>C | (p.?) | - | U | generalized RP (1) |

| c.533A>G | p.(Tyr178Cys) | Intradiscal (2nd extracellular loop) | 2 | generalized RP (1) |

| c.551A>G | p.(Gln184Arg) | Intradiscal (2nd extracellular loop) | U/P2 | generalized RP (1) |

| c.557C>G | p.(Ser186Trp) | Intradiscal (2nd extracellular loop) | 2 | generalized RP (1) |

| c.560G>C | p.(Cys187Ser) | Intradiscal (2nd extracellular loop) | 2 | generalized RP (1) |

| c.568G>A | p.(Asp190Asn) | Intradiscal (2nd extracellular loop) | 2 | generalized RP (2)/sector RP (1) |

| c.800C>T | p.(Pro267Leu) | 6th alpha helix (TM6) | 2 | generalized RP (1) |

| c.937-2A>T | (p.?) | - | U | generalized RP (1) |

| c.1033G>C | p.(Val345Leu) | Cytoplasm (C-terminal) | 1 | N/A |

| c.1040C>T | p.(Pro347Leu) | Cytoplasm (C-terminal) | 1 | generalized RP (1) |

Variant class and phenotype correlation.

U, unclassified; P2, predicted class 2; N/A, not available.

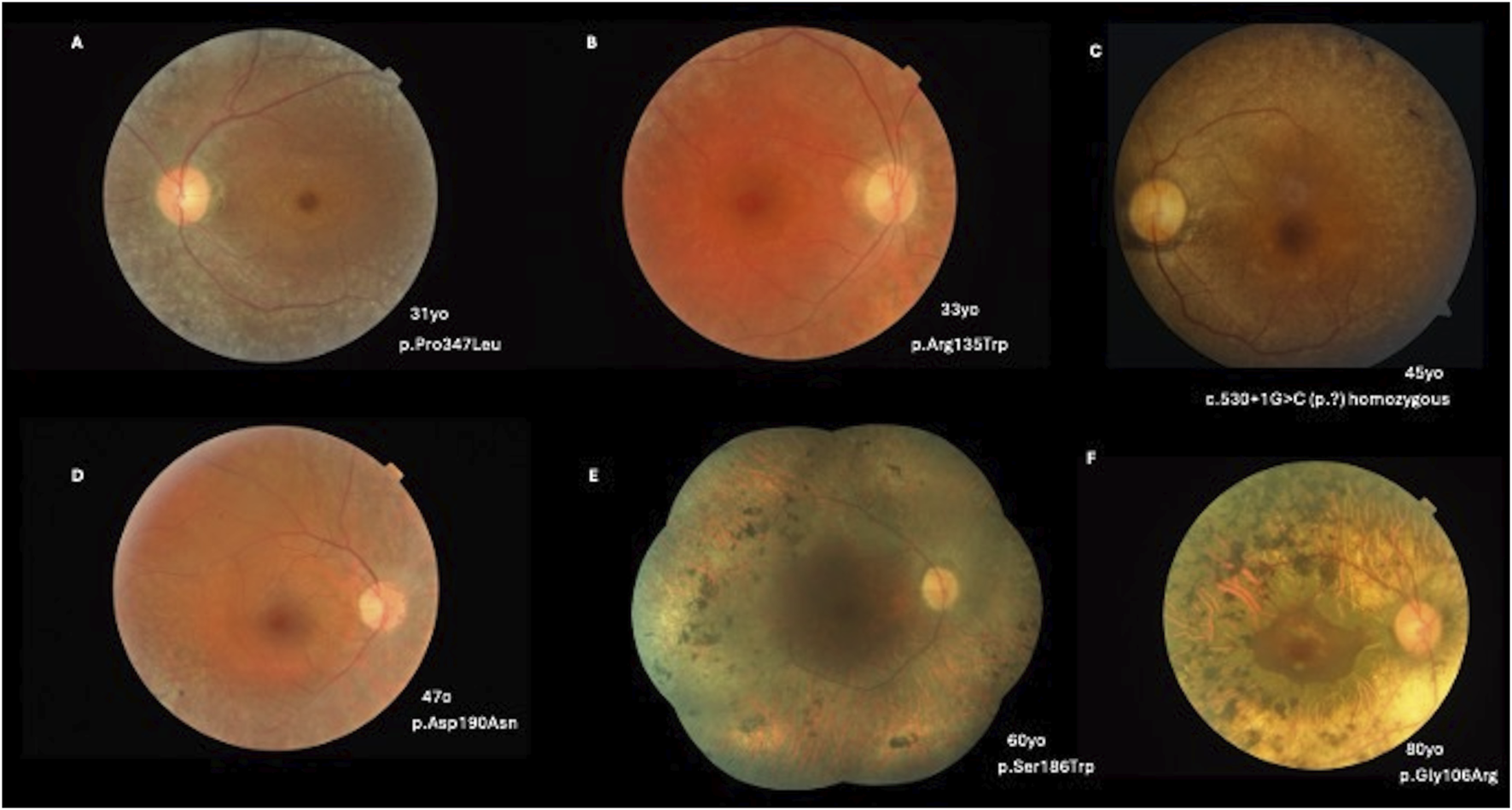

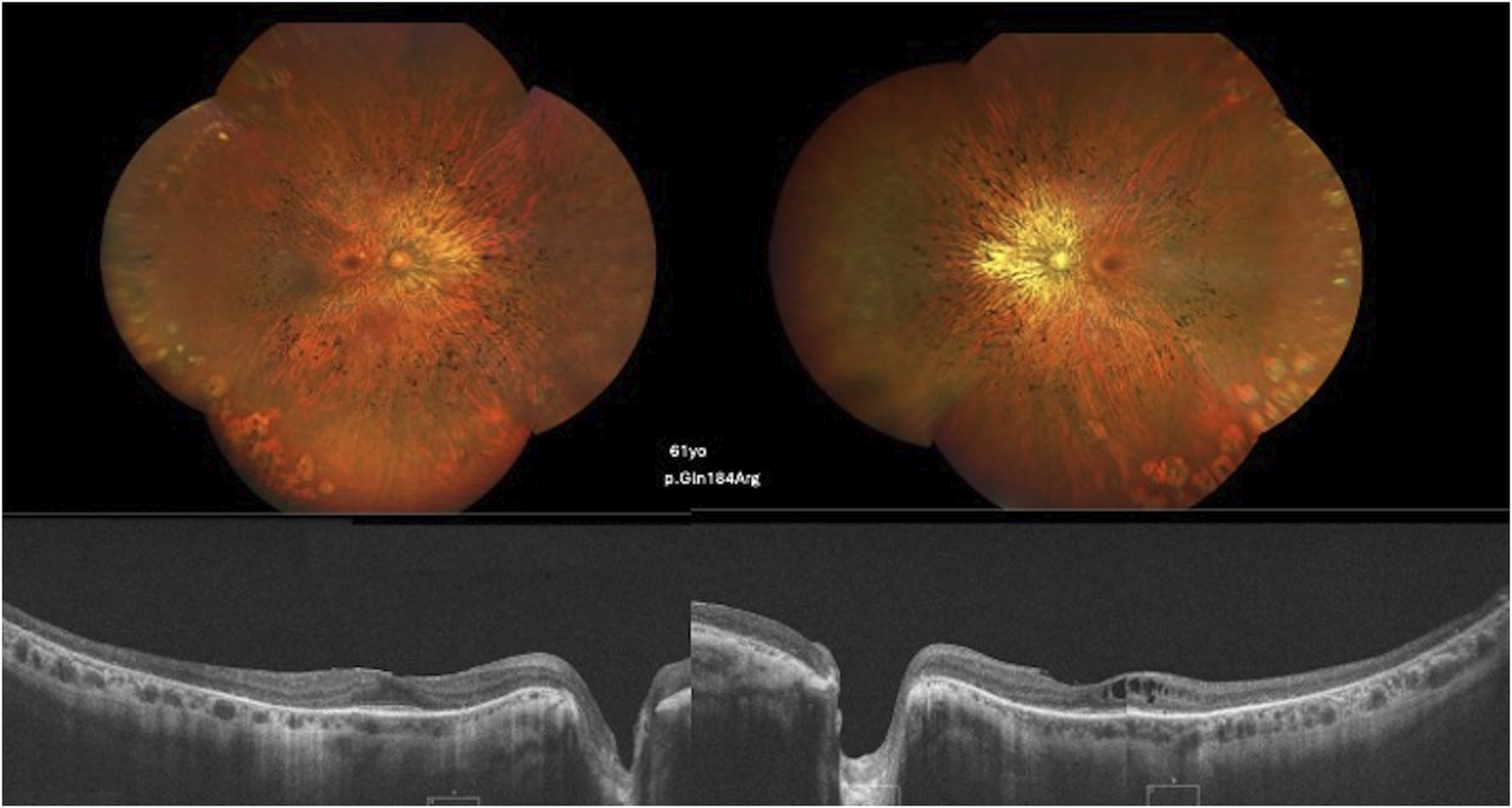

Retinal imaging

Thirty-two patients exhibited a generalized RP phenotype. Color fundus photography revealed common findings, including bone-spicule pigment deposits, a mottled retinal fundus, and vessel attenuation. Among these patients, seven presented with macular edema on optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans. Figures 2, 3 illustrate fundus images of RHO-associated RP patients in this study.

FIGURE 2

(A) A 31-year-old patient with a c.1040C>T, p.(Pro347Leu) variant presenting with BCVA of 20/25 OD and 20/30 OS, pigmentary mottling, and peripheral chorioretinal atrophy with bone-spicule hyperpigmentation. (B) A 33-year-old patient with a c.403C>T, p.(Arg135Trp) variant (BCVA: 20/40 in both eyes) with peripapillary and peripheral chorioretinal atrophy with narrowed vessels. (C) A 45-year-old patient with c.530+1G>C (p.?) in homozygosity (BCVA: 20/80 OD; 20/100 OS) and a more severe phenotype of classical RP. (D) A 47-year-old patient with a c.568G>A, p.(Asp190Asn) variant (BCVA: 20/40 in both eyes) with pigmentary mottling and peripheral chorioretinal atrophy. (E) A 60-year-old patient with a c.557C>G, p.(Ser186Trp) variant (BCVA: 20/400 in both eyes) with diffuse pigmentary bone-spicules and peripheral chorioretinal atrophy. (F) An 80-year-old patient with a c.316G>A, p.(Gly106Arg) variant (BCVA: 20/100 in both eyes) with advanced classical RP findings and preserved central vision in the macular area.

FIGURE 3

Color fundus and SD-OCT image of a 61-year-old patient carrying the c.551A>G, p.(Gln184Arg) variant showing diffuse classical RP findings and atrophy of the retinal layers, with the ellipsoid zone relatively preserved in the foveal area. CME is observed in the left eye.

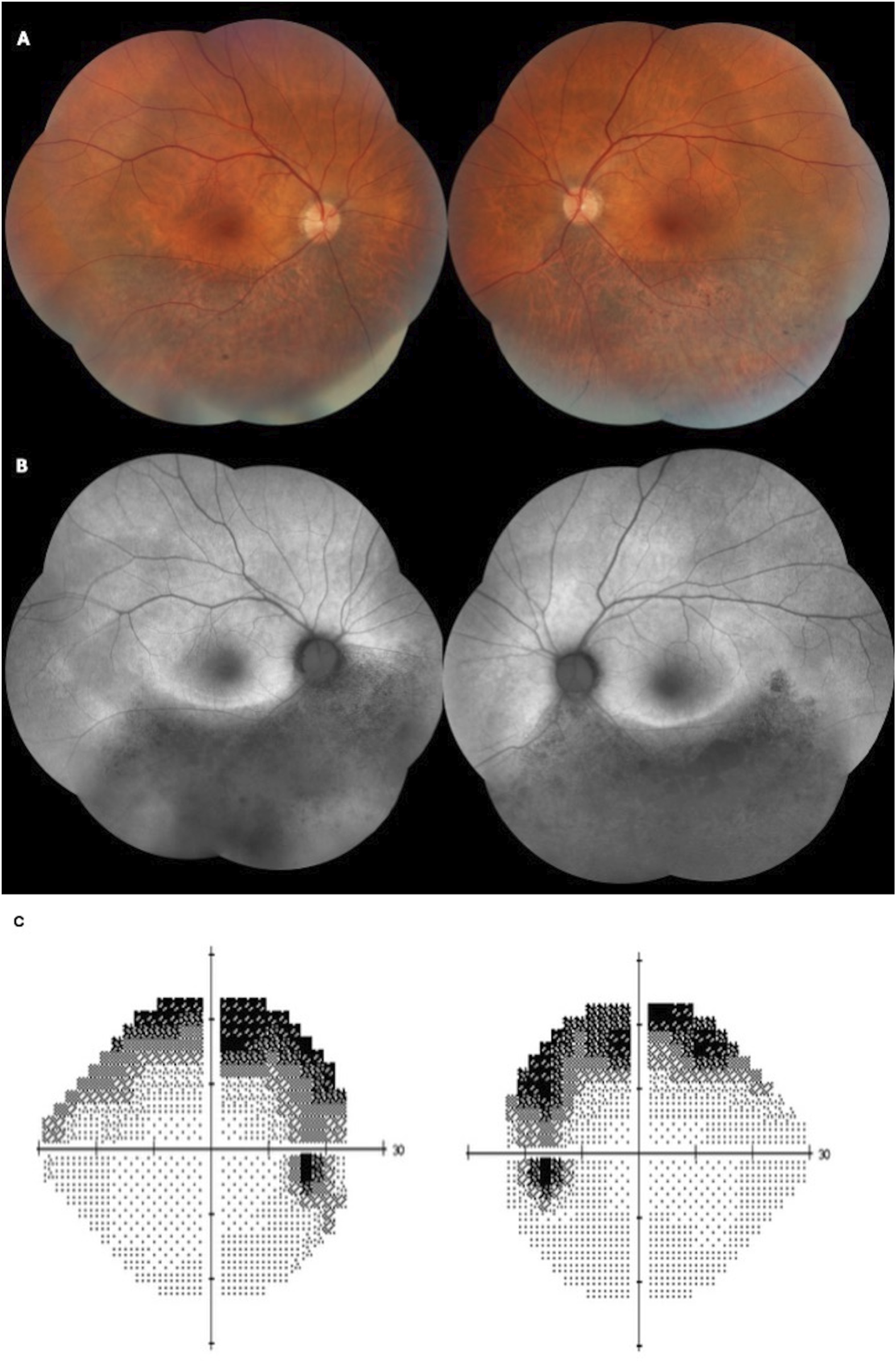

Six patients presented with the sector RP phenotype. The retinal fundus typically exhibited bone-spicule pigment deposits in the inferior retina. One patient presented with macular edema. Figure 4 presents the findings for sector RP.

FIGURE 4

Color fundus (A) and fundus autofluorescence (FAF) (B) of a 58-year-old patient presenting with BCVA of 20/25 in both eyes and sectoral inferior RP. The patient has the heterozygous variant c.568G>A, p.(Asp190Asn). (C) A Humphrey 24–2 grayscale visual field map of the same patient with bilateral and symmetrical superior visual field defects, showing anatomo-functional correlation with the fundus images.

Discussion

RHO-associated RP is one of the most common and well-characterized forms of adRP [28, 29]. Clinically, RHO-associated RP can present with distinct phenotypic patterns, ranging from diffuse retinal degeneration with early night blindness and peripheral vision loss to sector RP, in which degeneration is confined to specific retinal regions and disease progression is slower [30].

This study describes the first Brazilian cohort with RHO-associated RP, and the clinical and molecular spectrum related to retinal degeneration.

Approximately 60.0% of patients presented with a family history of RP. In total, 85% of patients had generalized RP, the most prevalent phenotype. Five patients had sector RP affecting the inferior retina, which is the most commonly affected retinal region. One hypothesis is that light exposure, particularly in the lower retinal regions that receive more direct illumination, contributes to disease progression [30]. In support of this hypothesis, studies using animal models of RHO-associated RP have shown that complete light deprivation can reduce the extent of outer retinal degeneration [31, 32].

Rhodopsin is a visual receptor composed of seven transmembrane helices connected by three extracellular loops on the intradiscal side and three intracellular loops on the cytoplasmic side [24]. Misfolding and ER retention are the most prevalent pathogenic mechanisms (Class 2) [33]. Class 2 variants were the most prevalent, with both generalized (63.0%) and sector (26.0%) RP phenotypes.

Several RHO-associated variants are responsible for sector RP; these are exclusively missense mutations, predominantly located in the intradiscal domain [30, 34]. Accordingly, the majority of patients in this cohort harbored intradiscal-domain missense variants. The exception was a sector RP patient with a previously unreported deletion variant in the second alpha-helix (TM2). The c.316G>A, p.(Gly106Arg) and c.568G>A, p.(Asp190Asn) variants, both frequently described as sector RP [10, 34], were identified in patients presenting with generalized RP. Similarly, the variant c.317G>T, p.(Gly106Val) was identified in two patients with sector RP and two with generalized RP. This is a previously catalogued variant without published clinical correlation (dbSNP rs1578278417). This missense variant is also a Class 2 variant, located intradiscally in the first extracellular loop and affecting codon 106. In this analysis, no variant was exclusive to the sector RP cases.

Cytoplasmic-domain variants are typically associated with a severe RP phenotype, characterized by the early rod and cone photoreceptor degeneration. In contrast, mutations affecting the extracellular domain are generally linked to a milder clinical presentation, with relatively preserved photoreceptor function and a slower rate of disease progression [35]. Class 1 variants in this cohort presented a mild phenotype, generalized RP, and early onset of symptoms. Class 2 variants are the most common, demonstrating a broader spectrum of clinical severity. Class 3 variants demonstrate early disease onset and a more severe phenotype. Variants in the N-terminal segment are sometimes associated with a relatively mild disease course, with RP developing later in life and slowly advancing symptoms [15]. In contrast, the patient described here with this variant location presented with generalized RP, high myopia, and early-onset symptoms, with relatively preserved vision until the sixth decade of life.

In this study, the c. 551A > G, p. (Gln184Arg) variant was the most frequent variant, found in seven patients from four families. The second most common variant was c.403C>T, p.(Arg135Trp), which was identified in five patients from two families. These two variants are present in European, American, and Asian populations. This is consistent with the literature, as missense mutations are the most common type of variant in the RHO gene [36].

RHO is one of the few genes that cause both adRPs and arRPs. The recessive form is typically associated with a complete loss of rhodopsin function, whereas the dominant form results from a gain-of-function and/or a dominant-negative mechanism [15]. To date, eight homozygous variants have been described in the RHO gene: c.448G>A, p.(Glu150Lys [37]; c.759G>T, p.(Met253Ile) [38]; c.931A>G, p.(Lys311Glu) [39]; c.482G>A, p.(Trp161*) [40]; c.745G>T, p.(Glu249*) [41]; c.936+1G>T (p.?) [42]; c.408C>A, p.(Tyr136*) [43]; and c.82C>T, p.(Gln28*) [23].

The underlying mechanisms by which missense mutations cause the recessively inherited form remain unclear; it is possible that missense changes are mild mutations that only become pathogenic when present on both alleles.

Aberrant splicing frequently generates premature termination codons (PTCs), which can result in the production of truncated proteins [44]. However, PTCs can trigger nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD), an essential mRNA quality-control mechanism that clears flawed transcripts. Typically, mRNA transcripts are targeted for accelerated degradation by NMD when a PTC is located 50–55 nucleotides downstream of the final exon-exon junction [45]. This process prevents the translation of transcripts into potentially harmful truncated proteins, although the efficiency of this process is currently unknown.

Hernan et al. described that the adRP-causing RHO variant c.937-1G>T abolishes the canonical splice-acceptor site in intron 4 [46]. Consequently, an aberrant exonic splice-site was used during transcription, leading to the production of a protein lacking 13 amino acids. In contrast, the c.936+1G>T variant, located at the donor site of the same intron, results in the complete skipping of exon 4 and causes the recessive form of the disease.

In our cohort, we identified the c.937-2A > T variant, affecting the splice-acceptor site of intron 4. This is a novel allele at a known pathogenic site (dbSNP rs1578281565). Similar to the previously reported c.937-1G>T variant, the c.937-2A>T variant causes adRP with a severe generalized phenotype. Notably, the transcript resulting from this variant is predicted to evade NMD. Since the variant is located in the final intron, any resulting PTC would lie downstream of the final exon-exon junction, thus failing to meet the canonical ∼50 nt rule for NMD targeting. Although the exact consequences require functional studies, this NMD evasion suggests the production of a truncated protein.

In the context of homozygous RHO variants, NMD activation may lead to a marked reduction or complete absence of rhodopsin mRNA, resulting in functional null alleles [47]. Retinal degeneration in these cases may arise from the loss of rhodopsin expression rather than from the dominant-negative or gain-of-function effects typically associated with certain heterozygous RHO cases [47].

Another previously reported splicing variant is c.531-2A>G [46, 48]. Due to its intron 2 location, this variant was initially anticipated to undergo NMD and, consequently, manifest as arRP. However, this specific allele has been documented in the Spanish population, where it is linked to full adRP penetrance [48]. In support of this dominant mechanism, in vitro studies conducted by Hernan et al. demonstrated that the transcripts generated as a consequence of the c.531-2A>G variant were not entirely abolished by NMD. Consequently, a truncated protein is expressed, representing the probable cause of the adRP phenotype [46].

In this Brazilian cohort, a previously unreported variant was located in intron 2 and affected the splice donor site. The homozygous c.530+1G>T variant was detected in one patient diagnosed with RP at 25 years of age. The patient presented with early-onset symptoms, including nyctalopia, starting at 5 years of age. Unlike the c.531-2A>G variant, the c.530+1G>T variant appeared to be completely targeted by NMD. This hypothesis is supported by the inheritance pattern: only patient who possesses both affected alleles (homozygous) presents with the phenotype, whereas patients who carry a single heterozygous variant, such as this specific patient’s mother, remains asymptomatic.

The c.1040C>T, p.(Pro347Leu) variant is the most frequently observed causative variant worldwide. It has also been identified in other ethnic groups [49]. In this Brazilian cohort, only one patient was identified with this variant, with generalized RP and a mild symptom phenotype.

RHO c.68C>A, p.(Pro23His) was the first variant reported at high frequency for this gene in the United States [2]. Based on a meta-analysis of diagnosed cases reported in the literature, the estimated clinical prevalence of adRP due to RHO c.68C>A, p (Pro23His) is approximately 2,000–3,000 patients [50]. In comparison, the number of individuals heterozygous for this variant in the United States was 6,176 [50].

Several techniques have been explored to treat RHO-associated retinopathy, many of which involve the c.68C>A, p.(Pro23His) variant [51–53], which has been comprehensively elucidated at the molecular level, with robust animal models available and a high potential clinical impact in the U.S. population.

However, the frequency of this variant is low in other populations. It appears to be extremely rare or even absent in populations outside the United States, with apparent geographical restrictions on this variant. A study of 300 Chinese families with RP found that, while RHO variants accounted for approximately 2.7% of cases, the c.68C>A, p.(Pro23His) variant was not reported in that population or in other Asian ethnic groups [54], such as Korean [55] and Japanese [56] cohorts, and only one case was reported in a large European cohort [57]. However, this was not observed in the Brazilian cohort.

This study has some limitations. One major limitation is the lack of functional assays to directly evaluate the molecular consequences of the identified RHO variants. Without experimental validation such as RNA expression analyses, minigene splicing assays, or protein quantification, it is impossible to conclusively determine whether the observed variants lead to RNA decay, aberrant splicing, or residual protein production. Functional investigations are imperative to confirm the molecular consequences of these variants and to clarify their contribution to phenotypic variability.

The genotype–phenotype correlations observed in this study should be interpreted as descriptive rather than causal or definitive associations, given the observational nature of the data and the limited sample size. Further genetic analyses of larger cohorts are required to better understand their pathophysiology.

In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into the clinical and genetic characteristics of RHO-associated RP within the Brazilian population while broadening the documented spectrum of disease-causing RHO gene variants.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Ethics Committee of the Federal University of São Paulo (protocol code 5.113.810, 19 November 2021).

Author contributions

RA, FM, GR, RR, and JS conducted data curation, formal analysis, and investigation. RA and FM wrote the manuscript. DM, MS, and OZ contributed to the review and editing process. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was supported in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) – Brazil, finance code 001.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ebm-journal.org/articles/10.3389/ebm.2026.10893/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

NathansJHognessDS. Isolation, sequence analysis, and intron-exon arrangement of the gene encoding bovine rhodopsin. Cell (1983) 34(3):807–14. 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90537-8

2.

DryjaTPMcGeeTLHahnLBCowleyGSOlssonJEReichelEet alMutations within the rhodopsin gene in patients with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. N Engl J Med (1990) 323(19):1302–7. 10.1056/NEJM199011083231903

3.

DryjaTPMcGeeTLReichelEHahnLBCowleyGSYandellDWet alA point mutation of the rhodopsin gene in one form of retinitis pigmentosa. Nature (1990) 343(6256):364–6. 10.1038/343364a0

4.

HartongDTBersonELDryjaTP. Retinitis pigmentosa. The Lancet (2006) 368(9549):1795–809. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69740-7

5.

KaraliMTestaFDi IorioVTorellaAZeuliRScarpatoMet alGenetic epidemiology of inherited retinal diseases in a large patient cohort followed at a single center in Italy. Sci Rep (2022) 12(1):20815. 10.1038/s41598-022-24636-1

6.

LandrumMJLeeJMBensonMBrownGRChaoCChitipirallaSet alClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Res (2018) 46(D1):D1062–7. 10.1093/nar/gkx1153

7.

BatemanAMartinMJOrchardSMagraneMAdesinaAAhmadSet alUniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res (2025) 53(D1):D609–17. 10.1093/nar/gkae1010

8.

Franklin by Genoox. Franklin by genoox. Available online at: http://franklin.genoox.com (Accessed October 25, 2025).

9.

Coco-MartinRMDiego-AlonsoMOrduz-MontañaWASanabriaMRSanchez-TocinoH. Descriptive study of a cohort of 488 patients with inherited retinal dystrophies. Clin Ophthalmol (2021) 15:1075–84. 10.2147/OPTH.S293381

10.

BalliosBGPlaceEMMartinez-VelazquezLPierceEAComanderJIHuckfeldtRM. Beyond sector retinitis pigmentosa: expanding the phenotype and natural history of the rhodopsin gene codon 106 mutation (Gly-to-Arg) in autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Genes (Basel) (2021) 12(12):1853. 10.3390/genes12121853

11.

NguyenXTATalibMvan CauwenberghCvan SchooneveldMJFioccoMWijnholdsJet alClinical characteristics and natural history of rho-associated retinitis pigmentosa. Retina (2021) 41(1):213–23. 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002808

12.

HofmannKPLambTD. Rhodopsin, light-sensor of vision. Vol. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. (2023). 93, 101116. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2022.101116

13.

ComitatoADi SalvoMTTurchianoGMontanariMSakamiSPalczewskiKet alDominant and recessive mutations in rhodopsin activate different cell death pathways. Hum Mol Genet (2016) 25:2801–12. 10.1093/hmg/ddw137

14.

RichardsSAzizNBaleSBickDDasSGastier-FosterJet alStandards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet Med (2015) 17(5):405–24. 10.1038/gim.2015.30

15.

AthanasiouDAguilaMBellinghamJLiWMcCulleyCReevesPJet alThe molecular and cellular basis of rhodopsin retinitis pigmentosa reveals potential strategies for therapy. Prog Retin Eye Res. (2018) 62:1–23. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.10.002

16.

VilelaMAMenna BarretoRKMenna BarretoPKSallumJMMatteviVS. Novel codon 15 RHO gene mutation associated with retinitis pigmentosa. Int Med Case Rep J (2018) 11:339–44. 10.2147/IMCRJ.S179105

17.

RodriguezJAHerreraCABirchDGDaigerSP. A leucine to arginine amino acid substitution at codon 46 of rhodopsin is responsible for a severe form of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Hum Mutat (1993) 2(3):205–13. 10.1002/humu.1380020309

18.

RousharFJMcKeeAGKuntzCPOrtegaJTPennWDWoodsHet alMolecular basis for variations in the sensitivity of pathogenic rhodopsin variants to 9-cis-retinal. J Biol Chem (2022) 298(8):102266. 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102266

19.

DryjaTPMcEvoyJAMcGeeTLBersonEL. Novel rhodopsin mutations Gly114Val and Gln184Pro in dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2000) 41(10):3124–7.

20.

YuYXiaXLiHZhangYZhouXJiangH. A new rhodopsin R135W mutation induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol (2019) 234(8):14100–8. 10.1002/jcp.28100

21.

ChuangJZVegaCJunWSungCH. Structural and functional impairment of endocytic pathways by retinitis pigmentosa mutant rhodopsin-arrestin complexes. J Clin Invest (2004) 114(1):131–40. 10.1172/JCI21136

22.

BehnenPFellineAComitatoADi SalvoMTRaimondiFGulatiSet alA small chaperone improves folding and routing of rhodopsin mutants linked to inherited blindness. iScience (2018) 4:1–19. 10.1016/j.isci.2018.05.001

23.

WangJXuDZhuTZhouYChenXWangFet alIdentification of two novel RHO mutations in Chinese retinitis pigmentosa patients. Exp Eye Res (2019) 188:107726. 10.1016/j.exer.2019.107726

24.

AzamMJastrzebskaB. Mechanisms of rhodopsin-related inherited retinal degeneration and pharmacological treatment strategies. Cells (2025) 14(1):49. 10.3390/cells14010049

25.

BeryozkinALevyGBlumenfeldAMeyerSNamburiPMoradYet alGenetic analysis of the rhodopsin gene identifies a mosaic dominant retinitis pigmentosa mutation in a healthy individual. Invest Opthalmology and Vis Sci (2016) 57(3):940–7. 10.1167/iovs.15-18702

26.

Sancho-PelluzJTosiJHsuCWLeeFWolpertKTabacaruMRet alMice with a D190N mutation in the gene encoding rhodopsin: a model for human autosomal-dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Med (2012) 18(1):549–55. 10.2119/molmed.2011.00475

27.

JonesBWKondoMTerasakiHWattCBRappKAndersonJet alRetinal remodeling in the Tg P347L rabbit, a large‐eye model of retinal degeneration. J Comp Neurol (2011) 519(14):2713–33. 10.1002/cne.22703

28.

XiaoTXieYZhangXXuKZhangXJinZBet alVariant profiling of a large cohort of 138 Chinese families with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Front Cell Dev Biol (2021) 8:629994. 10.3389/fcell.2020.629994/full

29.

KoyanagiYAkiyamaMNishiguchiKMMomozawaYKamataniYTakataSet alGenetic characteristics of retinitis pigmentosa in 1204 Japanese patients. J Med Genet (2019) 56(10):662–70. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2018-105691

30.

XiaoTXuKZhangXXieYLiY. Sector retinitis pigmentosa caused by mutations of the RHO gene. Eye (2019) 33(4):592–9. 10.1038/s41433-018-0264-3

31.

NaashMLPeacheyNSLiZYGryczanCCGotoYBlanksJet alLight-induced acceleration of photoreceptor degeneration in transgenic mice expressing mutant rhodopsin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (1996) 37(5):775–82.

32.

IwabeSYingGSAguirreGDBeltranWA. Assessment of visual function and retinal structure following acute light exposure in the light sensitive T4R rhodopsin mutant dog. Exp Eye Res (2016) 146:341–53. 10.1016/j.exer.2016.04.006

33.

BighinatiAAdaniEStanzaniAD’AlessandroSMarigoV. Molecular mechanisms underlying inherited photoreceptor degeneration as targets for therapeutic intervention. Front Cell Neurosci (2024) 18:1343544. 10.3389/fncel.2024.1343544

34.

VerdinaTGreensteinVCTsangSHMurroVMuccioloDPPasseriniIet alClinical and genetic findings in Italian patients with sector retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Vis (2021) 27:78–94.

35.

BersonELRosnerBWeigel-DiFrancoCDryjaTPSandbergMA. Disease progression in patients with dominant retinitis pigmentosa and rhodopsin mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2002) 43(9):3027–36.

36.

ManianKVLudwigCHZhaoYAbellNYangXRootDEet alA comprehensive map of missense trafficking variants in rhodopsin and their response to pharmacologic correction (2025). 10.1101/2025.02.27.640335

37.

AzamMKhanMIGalAHussainAShahSTAKhanMSet alA homozygous p.Glu150Lys mutation in the opsin gene of two Pakistani families with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Vis (2009) 15:2526–34.

38.

CollinRWJvan den BornLIKleveringBJde Castro-MiróMLittinkKWArimadyoKet alHigh-resolution homozygosity mapping is a powerful tool to detect novel mutations causative of autosomal recessive RP in the Dutch population. Invest Opthalmology and Vis Sci (2011) 52(5):2227–39. 10.1167/iovs.10-6185

39.

ZhangFZhangQShenHLiSXiaoX. Analysis of rhodopsin and peripherin/RDS genes in Chinese patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Yan Ke Xue Bao (1998) 14(4):210–4.

40.

KartasasmitaAFujikiKIskandarESovaniIFujimakiTMurakamiA. A novel nonsense mutation in rhodopsin gene in two Indonesian families with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmic Genet (2011) 32(1):57–63. 10.3109/13816810.2010.535892

41.

RosenfeldPJCowleyGSMcGeeTLSandbergMABersonELDryjaTP. A null mutation in the rhodopsin gene causes rod photoreceptor dysfunction and autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet (1992) 1(3):209–13. 10.1038/ng0692-209

42.

GreenbergJRobertsLRamesarR. A rare homozygous rhodopsin splice-site mutation: the issue of when and whether to offer presymptomatic testing. Ophthalmic Genet (2003) 24(4):225–32. 10.1076/opge.24.4.225.17235

43.

ZhangQXuMVerriottoJDLiYWangHGanLet alNext-generation sequencing-based molecular diagnosis of 35 Hispanic retinitis pigmentosa probands. Sci Rep (2016) 6(1):32792. 10.1038/srep32792

44.

LewisBPGreenREBrennerSE. Evidence for the widespread coupling of alternative splicing and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2003) 100(1):189–92. 10.1073/pnas.0136770100

45.

MaquatLE. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: splicing, translation and mRNP dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2004) 5(2):89–99. 10.1038/nrm1310

46.

HernanIGamundiMJPlanasEBorràsEMaserasMCarballoM. Cellular expression and siRNA-Mediated interference of rhodopsin cis -Acting splicing mutants associated with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Opthalmology and Vis Sci (2011) 52(6):3723–9. 10.1167/iovs.10-6933

47.

Roman-SanchezRWenselTGWilsonJH. Nonsense mutations in the rhodopsin gene that give rise to mild phenotypes trigger mRNA degradation in human cells by nonsense-mediated decay. Exp Eye Res. (2016) 145:444–9. 10.1016/j.exer.2015.09.013

48.

Fernandez‐San JosePBlanco‐KellyFCortonMTrujillo‐TiebasMGimenezAAvila‐FernandezAet alPrevalence of Rhodopsin mutations in autosomal dominant Retinitis Pigmentosa in Spain: clinical and analytical review in 200 families. Acta Ophthalmol (2015) 93(1). 10.1111/aos.12486

49.

ZhangXLLiuMMengXHFuWLYinZQHuangJFet alMutational analysis of the rhodopsin gene in Chinese ADRP families by conformation sensitive gel electrophoresis. Life Sci (2006) 78(13):1494–8. 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.07.018

50.

LeendersMGaastraMJayagopalAMaloneKE. Prevalence estimates and genetic diversity for autosomal dominant Retinitis Pigmentosa due to RHO, c.68C>A (p.P23H) variant. Am J Ophthalmol (2024) 268:340–7. 10.1016/j.ajo.2024.08.038

51.

DiakatouMManesGBocquetBMeunierIKalatzisV. Genome editing as a treatment for the Most prevalent causative genes of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Int J Mol Sci. (2019) 20(10). 10.3390/ijms20102542

52.

GiannelliSGLuoniMCastoldiVMassiminoLCabassiTAngeloniDet alCas9/sgRNA selective targeting of the P23H Rhodopsin mutant allele for treating retinitis pigmentosa by intravitreal AAV9.PHP.B-based delivery. Hum Mol Genet (2018) 27(5):761–79. 10.1093/hmg/ddx438

53.

Daich VarelaMGeorgiadisAMichaelidesM. Genetic treatment for autosomal dominant inherited retinal dystrophies: approaches, challenges and targeted genotypes. Br J Ophthalmol (2023). 107:1223–30. 10.1136/bjo-2022-321903

54.

LuoHXiaoXLiSSunWYiZWangPet alSpectrum-frequency and genotype–phenotype analysis of rhodopsin variants. Exp Eye Res (2021) 79:203. 10.1186/s13690-021-00714-0

55.

JungYHKwakJJJooKLeeHJParkKHKimMSet alClinical and genetic features of Koreans with retinitis pigmentosa associated with mutations in rhodopsin. Front Genet (2023) 29:14. 10.3389/fgene.2023.1240067

56.

TsutsuiSMurakamiYFujiwaraKKoyanagiYAkiyamaMTakedaAet alGenotypes and clinical features of RHO-associated retinitis pigmentosa in a Japanese population. Jpn J Ophthalmol (2024) 68(1):1–11. 10.1007/s10384-023-01036-0

57.

Daich VarelaMRomo-AguasJCGuarascioRZiakaKAguilaMHauKLet alRHO-associated retinitis pigmentosa: Genetics, phenotype, natural history, functional assays, and animal model - in preparation for clinical trials. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2025) 66(9):69. 10.1167/iovs.66.9.69

Summary

Keywords

autosomal dominant, genotype-phenotype, retinal dystrophy, retinitis pigmentosa, rhodopsin

Citation

Amaral RAS, Zin OA, Resende RG, Moraes DN, Salles MV, Rodrigues GD, Motta FL and Sallum JMF (2026) Expanding the clinical and genetic spectrum of RHO-associated retinitis pigmentosa. Exp. Biol. Med. 251:10893. doi: 10.3389/ebm.2026.10893

Received

13 November 2025

Revised

30 December 2025

Accepted

12 January 2026

Published

04 February 2026

Volume

251 - 2026

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Amaral, Zin, Resende, Moraes, Salles, Rodrigues, Motta and Sallum.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Juliana M. F. Sallum, juliana@pobox.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.